|

|

|

|

Risk Management The CGL & pollution liability Court cases indicate there are still some lingering questions about when coverage applies By Donald S. Malecki, CPCU Many years ago, one of the common claim issues having to do with commercial general liability was over bodily injury and property damage arising from loading and unloading of vehicles. While many of these arguments have been eliminated with the introduction of the 1986 CGL forms and the definition of “loading and unloading,” some questions continue to linger. From the standpoint of a CGL policy, no coverage applies while (1) the property is in movement into or onto an aircraft, watercraft or auto, (2) in or on the aircraft, watercraft or auto, or (3) the property is in movement from the aircraft, watercraft or auto to the place where it is finally delivered. One of the exceptions to the loading and unloading exclusion of CGL forms is movement of property by means of a mechanical device, other than a hand truck, that is not attached to the aircraft, watercraft or auto. Although the definition of loading and unloading appears to be straightforward, arguments still arise. In Continental Insurance Co. v. American Motorists Company, 524 S.E.2d 607 (Ct. App. Ga. 2000), the court held that a hydraulic pallet jack was not a hand truck. The CGL policy therefore covered an injury that occurred while the truck was being unloaded with the jack, which was not attached to the truck, because it was a mechanical device. Another area that appears to be problematic has to do with loading and unloading of pollutants. The reason is that the standard CGL policy, unendorsed with any pollution exclusion endorsement, excludes pollution-related events while the pollutants are being loaded or unloaded onto a vehicle, whether it is an auto, aircraft or watercraft, but not afterwards. Since 1986 when the plain English (and easy-to-read) liability provisions were first introduced, the pollution exclusion of policies makes an exception under CGL provisions for pollution-related events that take place after the unloading process has been completed. Unfortunately, some people either do not understand this or they would rather fight that concept rather than pay. In West American Insurance Company v. Johns Brothers, inc., et al., 435 F. Supp. 2d 511 (U.S. Dist. Ct. E.D. Va. 2006,) the heating oil supplier not only supplied heating oil but also maintained its clients’ heating systems pursuant to a contract. The underlying damage prompting a lawsuit against it in this case occurred as a result of a corroded oil return line that started leaking oil between October 2004 and the end of January 2005. During the period, the customer repeatedly contacted the oil supplier complaining of oil odors inside the house. The oil supplier made several visits to the house to monitor the heating system, make oil deliveries and respond to the complaints. After finding oil standing in the crawl space, the oil supplier closed off the house and made repairs. The oil supplier’s insurer filed a declaratory judgment action maintaining that the damages sustained by the customer were not covered by the oil supplier’s commercial general liability (CGL) policy. Both parties, the oil supplier and its insurer, agreed that coverage turned on application of the CGL policy’s pollution exclusion. The pertinent text of the pollution exclusion stated: 2. Exclusion

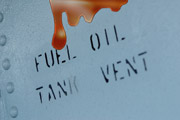

Three important questions The three questions that the court had to address here were: (1) Is heating oil a pollutant? (2) Did the parties intend to exclude heating oil from the definition of pollutant? (3) Was the oil supplier “performing operations” at the time of the oil leak? After considerable argument by both the oil supplier and its insurer, the court answered the first question by concluding that heating oil is a pollutant. The court stated, furthermore, that a plain meaning of the pollution exclusion in its entirety indicates that “fuels, lubricants and other operating fluids” are pollutants, and that there is no ambiguity in this respect. The second question posed a very interesting argument that, while novel, may generate some future argument in related scenarios, despite the fact the court was not convinced of it here. To state the argument simply, even if heating oil—for the sake of argument—is a pollutant, it should not be considered as such by the policy’s definition of “pollutant,” because it is viewed as a product with the premium based on sales of the oil product. In the words of the oil supplier, “a CGL for fuel oil dealers is worthless if fuel oil is excluded,” since the insurer cannot collect a premium based on the amount of oil sold and then claim that oil damage is excluded from coverage. It is like asking when does a product become a pollutant? In calculating the premium, the underwriter views the oil as a product. But when there is a claim, the claims person views the oil not as a product but as a pollutant. The court stated that even if it were to consider the fact that the premium was based in part on the nature of the oil supplier’s business, such fact does not override the express language of the pollution exclusion. Where the argument took a turn for the better, from the oil supplier’s perspective at least, was with the third question: Was the oil supplier “performing operations” at the time of the oil leak? This was an important question because even though oil is a pollutant, and bodily injury or property damage arising from the actual or alleged discharge, etc., of a pollutant is excluded, coverage could still apply so long as the oil supplier was not performing its operations at the time of the leak. While the oil supplier maintained that its operations were completed each time oil was delivered or heating system services were completed, its insurer countered with the argument that part (d) of the pollution exclusion referring to the words “performing operations,” did not convey a temporal requirement, i.e., present versus past activities. Even if it did convey such an intent, the insurer added, the oil supplier was performing operations at the time of property damage because it delivered oil on its own schedule and was acting under a service contract that required year-long monitoring and maintenance. The Achilles’ heel What convinced the court that part (d) of the pollution exclusion contains a temporal element was when it compared this part to three other parts of the exclusion. Notably, parts (a) and (b) refer to pollution on a site “which is or was at any time owned or occupied” by the insured, or land “which is or was at any time used by the insured for storing or disposing of waste.” On the other hand, part (d) refers to a location where the insured, or those acting on the insured’s behalf “are performing operations.” The fact that preceding parts (a) and (b) of the exclusion expressly encompass both past and present activities, whereas part (d) uses language to suggest present activities plainly established, from the court’s perspective, that a temporal element is intended in part (d) of the exclusion. Conclusion What is truly amazing here is the extreme to which the insurer went to deny coverage dealing with a situation that is intended to be covered. The policy language referred to in this case is standard ISO wording that was introduced in 1986. With the introduction of 1986 policy provisions came a plethora of articles on various subjects including the pollution exclusion. In fact, one of the documents that circulated in insurance circles back then was a policy comparison produced by ISO. With reference to this particular exclusion, the comparison stated that the “revised pollution exclusion does not apply to damages arising out of the insured’s products or completed operations, nor to some other off-premises discharges of pollutants not specifically excluded under f.(1)(d).” In essence, when an operation is deemed completed, it means the insured is no longer “performing operations,” and therefore is outside the reach of the pollution exclusion. Instead of arguing that the part (d) of the pollution was not temporal, the insurer should have explored its denial with reference of the products-completed operations hazard definition having to do with when an operation is deemed to be completed, and the criteria of products liability coverage. This approach, however, might have been a weaker argument for the insurer. In fact, this claim was more of a products liability case than a completed operations case, particularly since the fuel oil supplier was dealing with a product and was charged for sales of its product for insurance purposes. Also, everyone in the insurance business knows, or should know, that once a product has been relinquished and the injury or damage occurs away from premises of the product seller, it’s a product. In any event, reading between the lines of this case, it becomes abundantly clear that if an oil supplier suffers an oil spill during the delivery process, coverage is excluded—unless the event is precluded from being excluded by law. With the attachment of the mandatory New York Change Endorsement CA 01 12 03 06, for example, coverage continues to apply under the business auto, truckers and motor carrier coverage forms. If the product is not something that can be considered a pollutant, coverage under the CGL policy, as opposed to the commercial auto policy, will hinge on when the bodily injury or property damage occurs. If it occurs during the process of loading, unloading or use of the vehicle, it is the commercial auto policy that needs to be addressed. Producers who have more than one of these fuel oil suppliers may want to consider placing coverage with insurers that provide special programs because a variety of other coverages also can be obtained often with little additional cost. Some insurers, for example, provide coverage for wrong or erroneous delivery of products, on-premises pollution cleanup, product contamin-ation, and loss of business income following damage to the vehicles. Unquestionably, producers are likely to be charged a certain percentage of their commission to have their insureds participate in these special programs. But the producer will still own the account. Another possibly strong advantage for writing coverage under special programs is that it is less likely that insurers will attempt to deny coverage where the possibility of coverage exists, particularly if the account enjoys a good loss history. This also makes good risk management sense, since when coverage is denied and the claim upheld, producers commonly are viewed as a source of making up for the losses. * The author |

|

|||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||