|

Why own when you can rent?

Before forming a captive, try renting a segregated cell

By Peter Mullen, ACII, ARM

Why own when you can rent? If I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard that catchy expression, I’d have at least fifty bucks by now!

And I get confused when people talk about rent-a-captive and segregated cell companies in the same breath. Is it the same thing? Seasoned

practitioners in the captive world tend to throw jargon around like it’s going out of fashion, and I find that the rent-a-captive arena has more than

its fair share. The purpose of this article is to demystify some of this jargon

and explore some good reasons for renting a captive instead of owning.

Over the past 10 years, the rent-a-captive concept has entered the mainstream of

alternative risk-financing methods and can now stand shoulder to shoulder with

any other. The principal reason for this is the widespread use of segregated

cell legislation in most captive domiciles, which allows the rent-a-captive

facility to legally segregate the assets and liabilities of each insured using

the facility.

This wasn’t always the case. Prior to legal segregation, most rent-a-captives operated

using contractual segregation and most buyers were perfectly happy with that.

By contractual segregation I mean that each program in the facility had a

separate reinsurance arrangement, usually providing specific and aggregate

protection for the insured’s program. Any policies issued or reinsurance assumed on behalf of the client

clearly described the risks being written, and this documentation was

referenced in a participation agreement confirming the risks being assumed on

behalf of the insured.

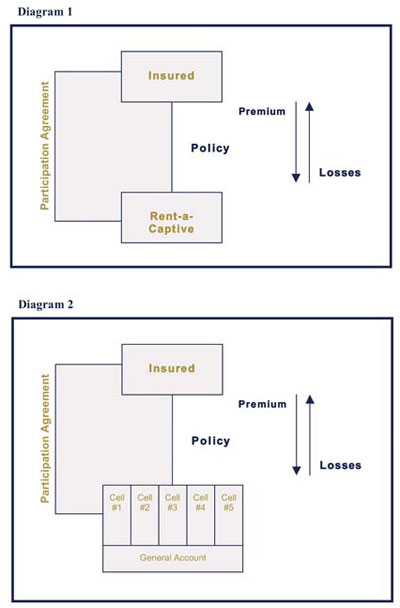

Diagram 1 illustrates a typical rent-a-captive operation and the

relationship of the parties involved. All of the contracts are tied together

through the participation agreement between the insured and the facility. The

participation agreement essentially says that the facility will account

separately for each client’s premium, losses, and investment income and will also include an indemnity in

favor of the facility should losses exceed the amount of funds available in the

cell. This indemnity is usually backed by collateral.

Diagram 2 illustrates a typical rent-a-captive operation using

segregated cells. As you can see, the transaction is effectively the same, with

the obvious important distinction being that the client has rented a specific

cell in the facility rather than just “space.”

Once you get over the fact that you don’t own the cell, the benefits of renting a cell versus owning your own captive

are pretty significant when weighed against the downsides of renting.

Clients who are considering a captive for the first time should give serious

thought to a segregated cell option, for the following reasons:

• The operating costs are significantly less than those involved in forming a

captive. A typical single-parent captive owned by a U.S. operation and insuring

its three casualty lines will operate with general and administrative expenses

in a range from roughly $120,000 to $150,000 per year. This includes management

fees, audit fees, legal fees, and domicile fees. For a similar deal, the

rent-a-captive will probably cost around $50,000, as the facility itself pays

one audit fee, one set of legal fees, and one domicile fee for the entire

facility. This is an annual savings of $70,000 to $100,000. That’s every year!

• Capital needed to operate the cell will be roughly the same as required for a

single-parent captive. A number of factors influence the amount of capital, not

the least of which is the insured’s risk appetite and the need to have a buffer in the event of poor loss

experience. Each domicile imposes a technical minimum capital requirement on

captives that is around 20% of premium. Domiciles will regulate rent-a-captive

facilities as they see fit, with some focusing only on the sponsor while others

look at each cell. As most facilities are “pass-through” facilities (i.e., they facilitate someone else taking risk), a number operate

on a “risk-free” basis and therefore are exempt from the domicile minimum capital requirement.

This is an area to watch closely for potential changes.

• Ease of setup and exit are often touted as advantages of a rent-a-captive

compared with an owned captive, and that’s certainly the case as far as setup is concerned. The extent of the benefit,

however, will depend on whether the domicile requires the facility owner to

have each new cell approved; if so, this process can take time.

• Some privately held companies have difficulty complying with a regulator’s request for confidential financial information when setting up a single-parent

captive. As they won’t be a director of the cell or the facility, the same disclosure requirements

don’t apply to the users of a rent-a-captive facility.

In addition to the potential cost and capital benefits outlined above, many of the good reasons for forming a captive apply equally to rent-a-captives:

• One P&L is maintained for all retained losses.

• Volatility among subsidiaries or divisions is reduced by having one central

funding mechanism.

• It facilitates a reward (and penalty) system for subsidiaries with good/bad

loss experience.

• Operating entities will improve loss reporting when they know a recovery is

available, which in turn will improve the quality of data available to make

management decisions.

• Operating entities will be unlikely to buy down their own deductibles when they

know a centralized funding mechanism is available at very cost-effective rates.

• If you cannot buy insurance at the right price or obtain the breadth of

coverage you need, or if it’s simply not available, a captive or cell is a good way to recognize the

existence of the exposure and pre-fund for it.

• A tax deduction is often available for premiums paid to a cell or captive,

assuming the program is structured properly.

When considering a cell or captive, it’s important also to evaluate the broader enterprise risk management benefit of

having a structured risk-financing plan in place. Stakeholders develop a greater confidence level in financial statements and data

generally, financial reporting risks are mitigated, and internal auditors can

look in just one place to find loss information and how it was accounted for.

What questions should you ask before renting a cell? The list below is not

exhaustive but should be helpful. It will also draw out some of the negatives of renting that should be

considered.

• Who owns the facility, and how long have they been in the business?

• Request a copy of the financials.

• Review the participation agreement in detail.

• What are the facility’s investments, and what control will I have over investment decisions (if any)?

• How is investment income calculated (and allocated if the facility is part of a

larger pool)?

• What happens if there is an investment loss?

• Exactly what fees am I being charged?

• How soon can I have my collateral/capital back, together with any distributions

for good experience?

• Do I have to take a distribution (can I leave the funds in the cell)?

• On what basis can collateral be drawn?

• What fees are charged during run-off?

• Obtain a sample financial statement for a cell. Will the statements provide the

information I need?

• How often will I be provided with financial statements?

• Will the cell be subject to U.S. taxes?

• Is U.S. Federal Excise Tax (FET) applicable to the transaction?

Segregated cell companies are now part of the mainstream when it comes to

alternative risk financing mechanisms. This purpose of this article is to

introduce a concept that continues to evolve. In the future, look out for the

possibility of the IRS treating cells as separate legal entities for U.S. tax

purposes and allowing them the ability to make a “D” election. Regulators also are paying more attention to individual cells, rather

than the facility sponsor, and this will result in additional regulatory

oversight. These are all indicators of the concept’s success and demonstrate that the rent-a-captive option is worthy of serious

consideration.

For more information:

Artex Risk Solutions, Inc.

Web site: www.artexrisk.com

Peter Mullen, ACII, ARM, is executive vice president of Artex Risk Solutions,

Inc., which was formed in 2007 through the combination of Arthur J. Gallagher

(Bermuda), Innovative Risk Services, and Gallagher Captive Services. Based in

Bermuda, Artex serves as a consultant to retail agents in developing and

managing alternative risk solutions for their clients.

|