|

Going lean

Diversified Insurance "strips the fat" from workflows

By Elisabeth Boone, CPCU

With the automotive manufacturing industry in a worldwide slump, not many people today are looking to that sector of the economy for dynamic business ideas. One standout in that beleaguered industry is Toyota, which revolutionized the way vehicles are built with its just-in-time inventory management structure and its tireless commitment to eliminating waste in the manufacturing process.

For decades, Toyota and other Japanese manufacturers have waged war on inefficiency with an approach known as Lean Systems, in which simulations are used to identify bottlenecks that waste time, energy, and money. The success of the Lean Systems concept in streamlining manufacturing operations is piquing the curiosity of entrepreneurs in service-oriented firms who are intrigued by the idea of using Lean methods to “trim and tone” their own workflows.

That curiosity is what motivated Tom Carroll, president of Diversified Insurance Industries, Inc., of Baltimore, Maryland, to persuade his partners that a Lean Systems simulation might be a powerful tool for process improvement at their agency.

Established in 1969, Diversified Insurance employs some 75 insurance professionals and writes a full range of products through more than 40 carriers: commercial property and casualty; professional liability; surety bonds; homeowners, auto, boat, and umbrella; term, universal, and whole life; and health and disability insurance. With annual premium approaching $100 million, Diversified clearly was doing plenty of things right.

“We are a sales organization first and foremost, but sales are profitable only if leakage, in the form of waste, is kept in check,” Carroll says. “We were painfully aware of process inefficiencies in the agency and knew they needed to be addressed. I first learned about Lean Systems on a field trip my MBA group made to a local manufacturer of unmanned drones. Observing Lean principles in action was like watching synchronized swimming or a ballet,” he remarks.

Carroll’s enthusiasm intensified during subsequent visits to Diversified Insurance clients that had implemented Lean Systems: a direct marketer of custom-printed products, a machine shop, and a riding mower manufacturer. Seeing how Lean was helping business owners streamline operations in a variety of settings spurred Carroll to think about applying the concept at Diversified.

What is Lean?

The Lean concept, Carroll explains, is “a systematic approach to identifying and eliminating waste—non-value-added activities—through continuous improvement by flowing the product at the pull of the customer in pursuit of perfection.” (Pull means that the product or service is created and delivered to meet the expressed needs of the customer, whereas push describes the situation where a company tries to sell something it thinks or hopes the customer will want.)

In Japanese, the word for “continuous improvement” is kaizen. “Kai means ‘to take apart,’ and zen means ‘to make good,’” Carroll explains. Perfection is the ideal to which we aspire but which we cannot attain, he says; therefore, “kaizen is a journey to a destination we’ll never reach.”

Carroll’s first step on the journey was to obtain buy-in from his partners to run a Lean Systems simulation exercise at Diversified. Understandably, Executive Vice President Sal DiPietro and Senior Vice President Mike Papa had serious questions about “going lean.”

After all, Lean Systems was designed to improve efficiency in manufacturing operations rather than in service businesses like insurance. What reservations did the Diversified management team have about making the leap?

“Although Lean Systems was originally developed for use in manufacturing, we were not the first organization to think about applying the concepts in an office environment,” Carroll says. “In fact, books have been written on the topic, like Lean Production for the Office by Jim Thompson. Processes are processes, whether they involve material handling or the logistics of intangibles—like answering a phone, handling a claim, or analyzing a policy.

“That being said,” Carroll continues, “Lean in the office is not very common, and the introduction of any change in our operations is always the subject of intense debate and discussion. We spent a lot of time doing our homework.”

With agreement from DiPietro and Papa, Carroll arranged for a representative from the University of Maryland’s Technology Extension Service to visit the agency and conduct a Lean simulation with a core group of Diversified employees. (According to Carroll, every state has a technology extension service to help manufacturers analyze and streamline their processes; they are quasi-government entities that offer their services at extremely affordable rates.)

Not surprisingly, not everyone on the Diversified staff was eager to take part in the Lean kaizen simulation exercise. In selecting employees to participate, the management team chose both people who were enthusiastic about the Lean concept as well as those who were resistant to change. “It was more important to invite the resisters to participate than to actually convince them that the exercise was worthwhile,” Carroll comments.

It was even more important, Papa points out, to assure employees that the object of the exercise was to improve efficiency, not to cut payroll or eliminate jobs. “The idea is to be lean, not mean,” he says. “If implemented correctly, the Lean approach lets you increase profits without firing people. We told our employees, ‘The more we can increase profits, the more we can put in your 401(k).’”

Waging war on waste

As noted earlier, Lean Systems focuses on identifying and eliminating waste in a given process. The Lean simulation exercise is the means by which an organization learns how to achieve this objective.

Waste, Carroll says, was defined by Fuijo Cho of Toyota as “anything other than the minimum amount of equipment, materials, parts, space, and workers’ time that is absolutely essential to add value to the product.”

In practice, Papa says, “Lean Thinking employs a methodology called Value Stream Mapping (VSM), wherein every step in a process is broken down and ‘mapped’ from beginning to end. (See example above). Value is defined as anything for which a customer will pay. The VSM process helps illuminate end goals and identify points in the process where waste is interfering with reaching those goals.”

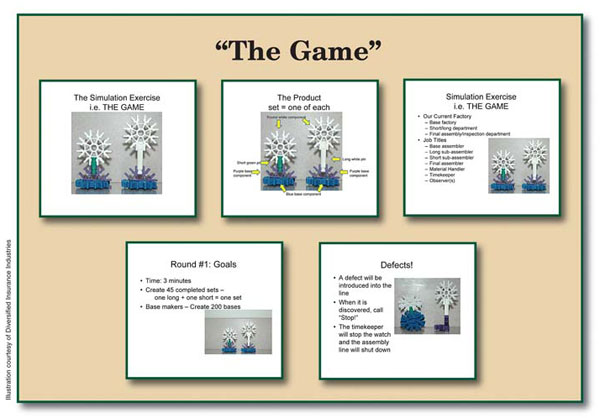

In Round One of the simulation, called the 10-Piece Push, participating employees were assigned jobs as if they were on a factory assembly line. (The 10 pieces were plastic widgets in various stages of assembly; the exercise was called a “push” simulation because the purpose was to make a product and “push” it to customers.) The “manufacturing” operation had three components: a base factory, a short/long department, and a final assembly/inspection department. The job titles were base assembler, long sub-assembler, short sub-assembler, final assembler, material handler, timekeeper, quality control supervisor, and observers.

“At the start of the exercise, it was total chaos, with widgets flying all over the place,” Carroll recalls with a laugh. “Every time the quality control person found a defect at the end of the process, she’d blow her whistle and the process had to start all over.”

In Round Two the participants switched to the pull method, producing items only on customer demand. “This phase was much smoother,” Papa remarks. “We saw the gains and analyzed the results, and we could clearly see the difference between push and pull.”

The third round of the simulation addressed waste issues. “We moved units closer together to save employees’ time, which freed them to do other value-added work,” Carroll says. “Instead of identifying defects at the end of the assembly line, we stopped the process and corrected the problem before proceeding to the next step. We saw a huge difference.”

Into action

For its first Lean project, Diversified decided to map the process it used to deliver certificates of insurance.

“For the purposes of Lean Systems, the simpler the process, the better, if for no other reason than what appears simple is often much more complicated,” Papa explains. “We chose the certificate process first because we thought it was a ‘low-hanging fruit’ project that would definitely succeed and that touched many of our 75 staff members in some way. We were surprised by how complicated that process turned out to be.”

Adds Carroll: “Think about it: Certificate requests can come from five different places, can be received by as many as five positions within the agency, and can be delivered in various ways to various constituents in varying amounts of time. Some requests are simple; others are crammed with complex specifications. It cost us $4 to prepare each certificate. By mapping the process, we discovered that we were spending $10,000 a year on paper, printing, mailing, shredding, and bad addresses.”

The Value Stream Map of Diversified’s original certificate process bore a disturbing resemblance to the schematics for one of Rube Goldberg’s hilariously complicated machines that were designed to make a process as time-consuming and inefficient as possible.

A map of the certificate “assembly line” as it would look with all the waste cut out shows a clean five-step process compared with the 49-step labyrinth depicted in the first map. “We’re not there yet,” Papa acknowledges. “But through the Lean concept of continuous improvement, we all see the goal; we see the waste, we’re all on the same page, and the process is much closer to the goal than before. Everyone along the way is aware of the bottlenecks, and that’s half the battle.”

Cultural shift

The Lean Systems approach has also produced impressive results in other areas of Diversified’s operation, DiPietro says.

“We’ve had kaizen events on billing, claims, placement of office machines, and green initiatives,” he says. “Implementation of some new procedures is being delayed while we shift processing models from a ‘silo’ model to a ‘shared services’ model, but savings are tangible in all areas where we’ve implemented Lean principles.

“Lean is a way of thinking that represents a cultural shift from a top-down to a bottom-up organizational structure,” DiPietro continues. “Everyone is encouraged to contribute to improving any process, whether or not that process has been formally ‘leaned out.’”

In support of the kaizen or continuous improvement culture Diversified is building, Carroll says, “We now have a robust suggestion system with a separate Web site where employees can submit their suggestions. A Lean Focus team meets monthly to review all of the suggestions. The team tries to implement every suggestion that makes sense,” he explains. “We use a 60% rule: If a suggestion makes more sense than not, there is intrinsic value in approving it.”

Although noting that “implementation is its own reward,” Carroll says, “We do reward the employee with the most implemented suggestions each quarter with a gift card and an agency-wide announcement. We also annually reward the employee who has made the most suggestions, whether or not they were implemented. For each implemented suggestion, the employee receives a personal thank-you note from me.”

What’s more, Carroll says, “I ambush people all the time to talk about how they’re doing a process and whether it’s lean. Our customers don’t pay us to make mistakes.”

Summing up

An organization that chooses to implement the Lean Systems approach is embarking on a commitment not simply to cut waste and boost profits, although those are key Lean goals.

“Our monetary savings have been substantial, even from our first project,” DiPietro asserts. “But our biggest accomplishment is the cultural shift that causes our employees to look at everything they do during a day through the lens of continuous improvement, and encourages them to question the process:

• Why do we do this? “Because it’s always been done this way” doesn’t cut it.

• Is there a better way?

• Does the customer really care? (We have two sets of customers: producers and policyholders.)

• Is this wasteful?

• Is this lean?

“Our biggest challenge,” DiPietro says, “is keeping up the momentum and instilling the kaizen culture in each new team member.”

For more information:

Diversified Insurance Industries, Inc.

Web site: www.dii-ins.com |