|

|

|

A new look at the Great Chicago Fire The fire that started Fire Prevention week and a focus on better underwriting

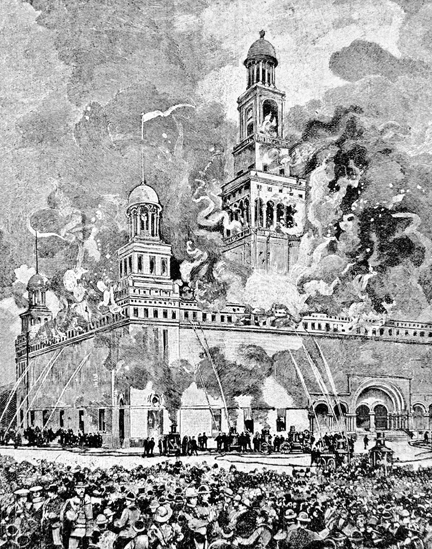

By Jack Payan, CPCU By October 1871, Chicago's rapidly growing business district lay between the Chicago River on the west and the lakefront, and had extended north of the river as well. The west side had been developed with numerous lumber and coal yards, and clutter from the accumulation of building supplies was scattered everywhere. It was a poor area with a plethora of frame houses, shacks, barns, sheds and outhouses, which were mostly unkempt. The city was a tinder box waiting to ignite. Chicago had already been plagued by a warehouse fire on September 30, and the beleaguered fire department had battled fires every day in the week preceding the big one: three on October 4; four on October 5 and five on October 6. On Saturday night, October 7, a fire started at 209 Canal Street and spread to the entire area from Jackson, Adams and Clinton Streets and the river. Reporting on the four-block blaze, the Chicago Tribune editorialized: "For days past, alarm has followed alarm, but the comparatively trifling losses have familiarized us to the pealing of the Courthouse bell, and we have forgotten that the absence of rain for three weeks had left everything in so dry and inflammable a condition that a spark might set a fire which could sweep from end to end of the city." Furthermore, the fire department was woefully undermanned, lacked necessary equipment and water supply, and the gallant firemen were simply worn out fighting fire after fire during that dreadful week. On October 8, a strong southwest wind was blowing across the city, which had suffered through an exceptionally dry summer and autumn. Only 0.74 inch of rain had fallen in the five weeks leading up to October 8. White caps were growing larger and larger on an angry Lake Michigan on an otherwise quiet Sunday evening. Professor Lapham of the Chicago Weather Bureau later commented, "A dry season, a strong wind and an accidental fire, whenever they occur together, will do the work." Catherine O'Leary, of 137 DeKoven Street, was about to become one of the most infamous characters in the city's long history as word spread that one of her cows kicked over a lantern, starting the fire. Mrs. O'Leary owned five cows that were all killed in the fire. She was quoted as saying that she never would leave a lantern in her barn. According to a Chicago Tribune article, Daniel "Peg Leg" Sullivan, a drayman, claimed on November 25, 1871 that he saw a cow start the October fire. However, "Sullivan's testimony contained many inconsistencies." There was speculation that he himself started the fire and was "covering up" his culpability. He had claimed to be just leaning on a fence in the neighborhood when he saw a flicker of light from the rear of O'Leary's property. He then ran toward the barn shouting "Fire! Fire! Fire!" Even more telling evidence turned up in the files of the Chicago Board of Underwriters, which contained a letter from a former Board member, T.C. Fetrow. The letter, dated September 1, 1943, maintains that the great holocaust did not even start on DeKoven Street. Fetrow wrote: "I happen to have the diaries of my father, C.J. Fetrow, 6 Woodland Park, who had an office at 109 Dearborn Street. These, of course, are the old numbers. In his diary I found the following: 'October 8, 1871—Big fire last night at Van Buren bridge, went to Clinton and north to Adams Street. Everything burned to the ground…. A sad day for Chicago. The whole city in flames, every building from Harrison Street north to Lincoln Park, east of the river, burned to the ground except Elevator B. Every bank, hotel, the Court House. Everything in ruins and almost every man a pauper. Greatest fire ever heard of, loss cannot be computed. Engines came from Milwaukee, Detroit and St. Louis.'" On October 19, 1871, C.J. Fetrow continued with: "The whole country on fire and there was great danger of it reaching Woodland Park. Loss is estimated at not less than $1 billion. No water or gas—everything in total darkness. Kerosene selling at one dollar per gallon and hard to find at any price. People carrying water five or six miles from the lake." T.C. Fetrow then added: "If the above actual eye-witness account is correct, I cannot see how the fire started on DeKoven Street as has been stated in other accounts, unless they moved DeKoven Street." Another interesting theory was published in the August 1996 Journal of the Czech & Slovak American Genealogy Society of Illinois which is published quarterly. The area around 137 DeKoven Street was the home of numerous Czech families at the time of the fire. Many eyewitness accounts were preserved, but by far the most interesting one was the account of Alexander Purer: "The O'Learys' barn had a window opening on the back yard of Krenek's Czech tavern…at Krenek's tavern there was a small dance hall, where on the fateful evening there was a party, organized as was the custom by the tavern-keeper. "After dancing, the young folks used to go out to the yard to cool off and they did not behave like angels…some of the frolicsome dancers could have carelessly thrown a burning cigarette or cigar into the open window. Several of our people considered the possibility that the fire had started this way, but it was kept for obvious reasons in great secrecy. If the rest of the people had heard of it, it could have brought down their wrath on our nationality." Michael Ahern of the Chicago Republic was the first person to publicly blame one of Mrs. O'Leary's cows, but he later admitted that his account was made up to sell papers.

Perhaps the most "far-out" theory was that the Chicago Fire and other devastating fires the same night in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, and Manistee, Michigan, ignited when pieces of a comet struck the earth. But then, who knows? Dateline: Chicago, October 9, 1871— "Chicago is burning! Up to this hour of writing (1 p.m. on Monday), the best part of the city is already in ashes! An area between six and seven miles in length, and nearly a mile in width, embracing the great business part of the city, has been burned over and now lies a mass of smoldering ruins! "All the principal hotels, all the public buildings, all the banks, all the newspaper offices, all the places of amusement, nearly all of the railroad depots, the water works, the gas works, several churches and thousands of private residences and stores have been consumed. The proud, noble magnificent Chicago of yesterday is today a mere shadow of what it was; and helpless before the still sweeping flames, the fear is that the entire city will be consumed before we shall see the end." (Chicago Evening Journal—Extra Edition.) The fire was virtually out of control from almost the moment it started. Ironically, O'Leary's house was untouched (although the barn burned down) as the fiery winds blew flames into a nearby row of tinder-dry wooden tenements. Their flaming wooden shingles were torn free by the wind and sailed upward and scattered embers everywhere. Soon the flames leaped across the Chicago River and engulfed buildings on Wells, LaSalle and Adams. The fire companies had been called out, but their efforts were practically useless as the flames and populace fled to the lakefront. The fire started to head south as well, but troops ordered into action by General Philip Sheridan blasted an effective firebreak, which thwarted the advancing flames. Next to catch fire was the open prairie north of the river, now known to us as Lincoln Park. In all, more than 2,000 acres were destroyed during the 36-hour period that the fire ran unchecked. Eventually the wind lessened and a heavy rain providentially brought the conflagration to an end. Five square miles of the heart of the city were destroyed along with 17,450 buildings. No fewer than 250 people were dead and at least 100,000 became homeless. No one can possibly know the total cost of the fire, but the figure of $200 million has been often mentioned in various accounts. Ironically, among those who suffered total losses of their homes was the expensive North LaSalle Street residence of Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard, the man who wrote the first insurance policy in the city back in 1834 and donated the first fire engine to the city as well. Although he had sold his insurance agency before the fire, he felt an obligation to his former clients whose fire losses were not paid by the various companies he formerly represented. As a result, he reportedly made up their losses with his own money and nearly went broke doing so. At the time of the fire, Hubbard was writing an autobiography but the fire destroyed his books, manuscripts and most of what he had written. Fortunately, with the aid of friends and family, and a sharp memory, he did complete a book, which was published two years after his death. His story is the story of the birth and adolescence of the city by the lake. Mayor William Ogden's magnificent neighboring mansion was also destroyed but his brother Mahlon's house, which was next door, was saved by the placing of wet blankets on the roof. The Newberry Library now occupies the latter site. "No city can equal now the ruins of Chicago, not even Pompeii, much less Paris," E.J. Goodspeed wrote after the fire. While Chicago struggled for survival, the insurance industry reeled from the calamitous impact of the fire. It was estimated that less than 50% of the damage was insured with a total of 182 insurance companies. Sixty-eight companies failed immediately and 83 were able to pay their losses only in part, leaving only 31 that met all of their obligations. It became glaringly obvious that the insurance industry was totally unprepared to deal with such a catastrophe. The Encyclopedia of Chicago stated: "But, by the most generous estimate, the insurance industry paid for less than a third of the total fire damage. Countless businesses and homeowners were denied their insurance claims and were never able to start over."

The Hartford Fire Insurance Company was one of the 31 companies that paid all of its claims, which totaled nearly $2 million. The company's total assets at the time were less than $1.7 million. Hartford's president, George Case, sent a telegram to every one of their agents stating: "The Old Hartford will promptly meet all of its obligations in Chicago and elsewhere as usual. Continue business and advance rates 50 to 100%." George Bissell, their Chicago general agent, saw his new LaSalle Street office destroyed along with all of the company's records. At 128 LaSalle, however, the important agency of Moore, Case, Lyman & Hubbard had its office. The firm had represented The Hartford since 1864. Although the agency's building was destroyed as well, its huge vault was not. "The vault in our office was intact," James H. Moore, the senior partner in the agency, wrote many years later, "but we didn't open it until Thursday afternoon because of the heat." The agency was able to match the street numbers of the destroyed buildings with the applicable insurance company. A schedule was created and the agency sent a courier to Joliet, Illinois, where the nearest operable telegraph office was located, to advise each of the agency's five companies of its total liability. The Hartford eventually paid $1,968,225 after borrowing money and issuing new stock. The company also rebuilt its Chicago office in December 1871. On the other hand, 72-year-old Providence Washington had assets totaling about $400,000.The company's losses in Chicago were $546,000 and their directors voted to pay 70.5 cents on the dollar. Earlier, in May 1871, those same directors voted a bonus of $1,000 to President Kingsbury. Director Martin Chapman of the Springfield Fire & Marine (founded in 1849 in Massachusetts) told his fellow directors in 1855 that "in the West there would be constantly the imminent danger of sweeping fires from the imperfect organization of fire departments, the inferior construction of buildings and the presence of wood exposures." A committee headed by Chapman recommended a reduction in the number of Western agencies, and the company responded by substantially reducing Western business. Nevertheless, Springfield F&M, which was one the earliest and most aggressive in developing business in the Western territories, sustained losses of $450,000 which they paid in full. They then assessed stockholders $65 per share to repair capital. Chicago agent C.H. Case was able to save all of his policy records just before his office was consumed by fire, and his major company, the INA, paid their $650,000 in claims in full. Other major companies to pay staggering losses in full were the Aetna which paid out $3,773,423; The Liverpool, London and Globe, $3,239,091; and the Home of New York, with losses also exceeding $3 million. Another major eastern underwriting company had a better experience. The Glens Falls Insurance Company (founded in 1849 in New York City) decided on January 11, 1870, to discontinue writing all business in the State of Illinois. Their president, Russell Mack Little, had visited the state and saw firsthand the hazards represented by the wooden buildings crowded against one another. He told his board of directors: "The rates were inadequate particularly for the conflagration hazard presented in the rapidly growing City of Chicago." The company had one loss—on a church—that was promptly paid. Prior to the holocaust the home offices of 14 insurance companies were located in Chicago. The sole survivor was the American Insurance Company, whose losses totaled $972,900, which were easily paid by the company. The American was originally organized and chartered in Freeport, Illinois; but by special act of the Illinois Legislature was permitted to move to Chicago along with its secretary and managing officer, C.L. Currier. Another Chicago-based insurance company, The Union Insurance and Trust Company, in 1870 elected to cease the business of insurance, reinsure its outstanding risks and engage in a general banking business under the banking provision of its charter. What a fortuitous business decision that proved to be. The Phoenix Insurance Company of Brooklyn, New York, was credited with being the first company to pay a claim resulting from the fire. October 12, 1871, was the date of payment. The event became a reality only because their agent, Robert S. Critchell, had gotten word to the home office through a friend who was traveling to LaPorte, Indiana. The friend sent a telegram from there and a representative arrived two days later from New York with the claim money. With the aid of more than $100 million in insurance settlements and relief funds from all over the United States and Europe, Chicago began to rebuild. The energy that had sparked the city's initial growth was regenerated after the fire and an entirely new, modern, better city emerged from the ashes. Wood was largely barred in the reconstruction process, and a fine progressive city of brick and stone was created. One of the few structures that survived the fire was the newly constructed Chicago Water Tower which still stands majestically on Michigan Avenue just south of the Chicago River. It is one of the most important icons in the city, as it has become the greatest memorial to the Great Fire.

Another icon is Fire King No. 1, the bright red hand pumper that Gurdon Hubbard purchased for the city in 1835. It has been fully restored and is now a main attraction in the Chicago History Museum. The unsung heroes of the fire were the Chicago firemen who so gallantly and selflessly battled the conflagration, which would ultimately change the entire face of the great city on the lake. The first Chicago fire fighting company was formed in 1832, three years before the city was incorporated. It wasn't until 1858 that the first paid department was organized. The first completely paid company was Engine Company #3 located at 225 South Michigan Avenue. DeKoven Street, near the former site of O'Leary's barn, is today well marked as the present site of the Chicago Fire Academy. The Insurance Times commented on the fact that 68 insurance companies nationally went into liquidation following the Great Chicago Fire. "The Chicago fire was godsent. It enabled them to fold the drapery of death around them and die with honor. Low rates, bad practices and imbecility had been doing their slow but sure work, and failure sooner or later was inevitable." Following the Great Fire, the Chicago Board of Underwriters became much more active than ever in their proclaimed goal to properly regulate the insurance business and promote fire safety in a city which had been poorly constructed with a fire department and a water supply which were simply inadequate. No organization recognized these glaring faults more than the CBU. The Board worked with city authorities in enforcing building codes with regular inspections. In 1874, the National Board of Fire Underwriters passed a resolution for all insurance companies to pull out of Chicago until reforms were completed. Fortunately, the aforementioned reforms negated the need for this radical resolution. It is no accident that during the calendar week that includes the 8th day of October each year, the entire nation observes Fire Protection Week. The commemorative event is a direct by-product of the Chicago Fire. The event is designed to keep the public informed of the disastrous effects of fire and to encourage fire prevention awareness across this great land. There have been many other disastrous fires in the United States over the years, but the Great Chicago Fire stands alone for its intensity, widespread destruction and its impact on a growing, vibrant metropolis. The author Jack Louis Payan, CPCU, is a Chicago native. After graduating from Eastern University and serving a brief stint as sports editor of the Mattoon Daily Journal Gazette, he entered the insurance business as a local independent agent in the Chicago area and remained in that capacity until retiring in 2006. He served as president of the Chicago Board of Underwriters, the Independent Insurance Agents of Illinois and the Independent Insurance Agents and Brokers of America. He is the only person ever to lead all three associations. He has authored many columns and articles on insurance subjects and, in 1991, served as co-editor and a contributing author to the book, Soaring With Eagles, a definitive history of the IIABA.

|

|||||||

| |||||||

| ©The Rough Notes Company. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a database or retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or by other means, except as expressly permitted by the publisher. For permission contact Samuel W. Berman. |